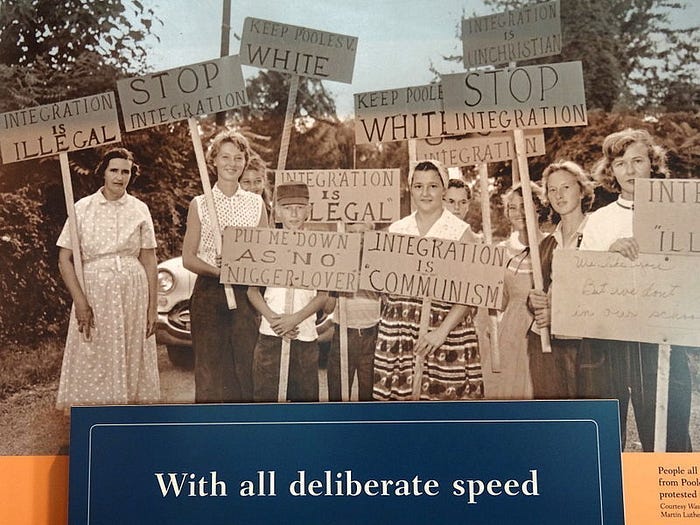

The “End of Segregation” Didn’t Go as Planned

What Happened After Brown v. Board of Education?

In 1951, Oliver Brown attempted to enroll his daughter Linda in the all-white Sumner School in Topeka, Kansas. Linda Brown was turned away because she was Black. Oliver filed a lawsuit claiming that Black schools weren’t equal to white schools and violated the “equal protection clause” of the 14th Amendment. The U.S. District Court agreed that public school segregation had a “detrimental effect upon the colored children and contributed to a sense of inferiority,” but let stand the “separate but equal doctrine enshrined in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. Plessy v. Ferguson has long been considered one of the worst decisions ever made by the Supreme Court, though Chief Justice William Rehnquist indicated he would have supported it as late as 1952.

The Brown lawsuit was combined with four other school desegregation cases and came before the Supreme Court as Brown v. Board of Education in 1952. The chief attorney for the plaintiffs was Thurgood Marshall with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. The NAACP had worked for several years to bring this issue before the Supreme Court and now had their chance.

The Court was divided on how to rule with Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson in favor of upholding segregation. Vinson died and was replaced by California Governor Earl Warren, appointed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Warren wrangled a unanimous decision out of the justices, striking down segregation in public schools.

“In the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” — Chief Justice Earl Warren

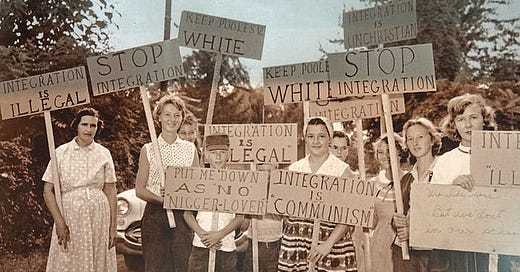

That should have been the end of the story; perhaps it was just the beginning of a long chapter in American history of attempts to uphold segregation that continue today. The first problem was the failure of the Supreme Court to define how school districts should go about desegregating. In 1955, they sent the issue back to lower courts, suggesting they act “with all deliberate speed,” which some states interpreted as meaning they could take as long as they wanted. Several Governors resisted the Supreme Court and insisted they would not comply.

“It is essential to the perpetuation of our Anglo-Saxon civilization that white supremacy be maintained and to maintain our civilization there is only one solution, and that is either by segregation within the United States or by the deportation of the entire Negro race.” — Theodore Bilbo, Governor of Mississippi

“I will never open the public schools as integrated institutions.” — Orval Faubus, Governor of Arkansas

“In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny … and I say … segregation now … segregation tomorrow … segregation forever.” — George Wallace, Governor of Alabama

“If necessary, we should close our schools for a month or a year or two years. It would be better to do that and have free children than slave children.” — Lester Maddox, Governor of Georgia

“Segregation in Texas will continue as long as I am governor.” — Allan Shivers, Governor of Texas

United States Senators joined in as well.

“All the laws of Washington and all the bayonets of the Army cannot force the Negro into our homes, into our schools, our churches and our places of recreation and amusement.” — Strom Thurmond, South Carolina

“There aren’t enough troops in the whole United States to make the white people of this state send their children to school with colored children.” — Herman Talmadge, Georgia

“Those who would mix little children of both races in our schools are following an illegal, immoral, and sinful doctrine….” — James O. Eastland, Mississippi

A Florida sheriff was the most succinct in his statement.

“Get those niggers out of school.” — Willis McCall, Lake County Florida

The initial reaction to Brown v. Board varied. Despite the harsh reaction of many politicians, many leaders accepted what was now the law of the land and made plans to integrate their schools. Using Virginia as an example, the Richmond Times-Dispatch initially asked for “a calm, unhysterical evaluation of the situation.” Dr. Dowell J. Howard, the Superintendent of Public Instruction, said, “We are trying to teach school children the law of the land, and we will abide by it. Virginia has always taken care of her problems, and I think she still has that ability.”

Weeks later, opinions consolidated, and the state came down fully against integration. The official newspaper of Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia in Charlottesville was blunt.

“We feel that the people of the South are justified in their bitterness concerning the decision. To many people, this decision is contrary to a way of life and violates the way in which they have thought since 1619.”

Virginia Senator Harry Byrd didn’t take Brown v. Board lying down, he called the opinion “the most serious blow that has yet been struck against the rights of the states in a matter vitally affecting their authority and welfare.” Byrd created a coalition of over 100 Southern politicians that signed onto his Southern Manifesto to resist integration.

We regard the decision of the Supreme Court in the school cases as a clear abuse of judicial power. It climaxes a trend in the Federal judiciary undertaking to legislate, in derogation of the authority of Congress, and to encroach upon the reserved rights of the States and the people.

The original Constitution does not mention education. Neither does the 14th amendment nor any other amendment. The debates preceding the submission of the 14th amendment clearly show that there was no intent that it should affect the systems of education maintained by the States.

The very Congress which proposed the amendment subsequently provided for segregated schools in the District of Columbia.

When the amendment was adopted, in 1868, there were 37 States of the Union. Every one of the 26 States that had any substantial racial differences among its people either approved the operation of segregated schools already in existence or subsequently established such schools by action of the same lawmaking body which considered the 14th amendment.

Though there has been no constitutional amendment or act of Congress changing this established legal principle almost a century old, the Supreme Court of the United States, with no legal basis for such action, undertook to exercise their naked judicial power and substituted their personal political and social ideas for the established law of the land.

This unwarranted exercise of power by the Court, contrary to the Constitution, is creating chaos and confusion in the States principally affected. It is destroying the amicable relations between the white and Negro races that have been created through 90 years of patient effort by the good people of both races. It has planted hatred and suspicion where there has been heretofore friendship and understanding.

With the gravest concern for the explosive and dangerous condition created by this decision and inflamed by outside meddlers:

We reaffirm our reliance on the Constitution as the fundamental law of the land.

We decry the Supreme Court’s encroachments on rights reserved to the States and to the people, contrary to established law and to the Constitution.

We commend the motives of those States which have declared the intention to resist forced integration by any lawful means. . . .

We pledge ourselves to use all lawful means to bring about a reversal of this decision which is contrary to the Constitution and to prevent the use of force in its implementation.

[Signed March 1956 by 19 Senators and 81 Representatives from the South] .

“If we can organize the Southern States for massive resistance to this order I think that, in time, the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South.” — Senator Harry Flood Byrd

United States Attorney General Herbert Brownell invited representatives from Southern states to find a resolution, but only three states, Virginia, Florida, and Mississippi, accepted his invitation. Brownell’s response was to draft the Civil Rights Act of 1957, which passed, though the language was weakened in the U.S. Senate. Virginia Governor Thomas B Stanley was firm in his defiance.

“I shall use every legal means at my command to continue segregated schools — Thomas B. Stanley

Take Virginia’s stance and spread it across most Southern states, many of whose political leaders signed onto the Southern Manifesto. The states were refusing to comply, and the federal government had yet to take a stand. The showdown came in Little Rock, Arkansas, where nine Black teenagers attempted to enroll at Little Rock Central High School. Governor Orval Faubus had called up the Arkansas National Guard to surround the school to prevent their entry. On September 4, 1957, the students were turned back when met by soldiers with raised rifles.

On September 23, 1957, the students returned, this time entering the school. They wound their way through a sea of anti-integration protesters and media. When the protesters realized the students had entered the school, violence broke out, and several of the media were attacked. School officials sent the “Little Rock Nine” home at lunchtime, in fear for their safety. The next day, President Eisenhower sent in paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division to escort the students. Federal troops got involved under an exception to the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, which was meant to keep federal troops from returning to protect the rights of the formerly enslaved.

Over the next few days, Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard, taking away the control of them from Governor Faubus. The following article published by Life magazine has several pictures worth viewing.

Little Rock Nine: Photos of a Civil Rights Triumph in Arkansas, 1957

This all played out on national television and with the “victory” of the federal government if forcing integration. Several other states began to see the light, though “all deliberate speed” allowed them to take their time. The Little Rock Nine faced a year of threats, taunting, and hazing from fellow students and adults, with eight of them finishing the school year at Little Rock Central.

With segregation underway, the impact on the Black community was now being fully felt. The separate but definitely unequal Black schools were staffed by Black educators and administrators who were less welcome at integrated schools than Black students. Black educators were dismissed, demoted, and in many cases, forced to resign when it came to finding places for them in integrated schools.

65 Years After ‘Brown v. Board,’ Where Are All the Black Educators?

“The majority of people in Topeka will not want to employ Negro teachers next year for white children. It is necessary for me to notify you now that your services will not be needed for next year.” — Wendell Godwin

In Mobley, Missouri, a Black school was closed down, leading to the dismissal of eleven certified teachers, including one Ph. D. They had more classroom hours and college credits than many of the white teachers that kept their jobs in the District. Seven Black teachers sued the school district, claiming their jobs were lost due to race. State courts sided with the school districts, and the Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

A Black principal in Georgia saw all his students transferred and was forced to accept a $3,000 reduction in pay. He was assigned to sit in a windowless room in an attic in the superintendent’s building. He eventually resigned in humiliation. In her book, The Lost Education of Horace Tate Uncovering the Hidden Heroes Who Fought for Justice in Schools, Vanessa Siddle Walker documented the unsung Black educators who fought for Black education in segregated and integrated schools.

When I was taught about Brown v. Board Of Education, it was presented as a victory that brought an end to segregated schools. It took federal troops in Arkansas and consent decrees across the country for integration to be meaningfully implemented in most regions of the country. There are areas as diverse as Mississippi and New York where segregated schools exist today; the 14th Amendment be damned.

One of the means to foil desegregation was for states to issue vouchers to parents to send their kids to private schools that didn’t accept non-white students. Tell me the same thing isn’t happening today, except that a few non-white students are permitted.

The Racist Origins of Private School Vouchers — Center for American Progress

Over 70 years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision was announced. Why is it that we’re still fighting for equality in education? Why?

I am a retired high school science teacher. For 34years I experienced how much our education systems are used to continue to deliberately segregate students using legal funding structures that limit the quality of education available to poor students of color as well as white students from poor families. The gatekeeping is built in at all levels - from pre-k to apprenticeship programs and other post secondary opportunities for gaining knowledge and skills. Brown vs. Board of Ed. is still being fought in school districts and other educational programs across the USA in 2025. The architects of Project 2025 are just the latest version of segregationists that want to destroy the equal rights of people to access a quality education so that they can pursue life, liberty and happiness.

I'm sharing this on other platforms. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and expertise with all of us.

White supremacy is a disease as old as America itself. All schools should be teaching and supporting the science that proves "races" do not exist within the total population of the human species. For biological reasons proximity to sunshine and potable water determined melanin levels for local populations over a period of centuries. But hatred is altogether different. Insecurity and doubt make people need to feel superior in order to soothe or at least quiet the internal conflict. Dr. King said, "Hate cannot drive out hate. Only love can do that."